As outlined in the Environment Act, the Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) policy outlines that habitats and environments affected by any new developments from April 2024 must now boost the nation’s biodiversity levels at a gain of 10% to leave no room for a net loss.

Within the BNG requirement, they outline a list of ‘irreplaceable habitats’ that are exempt from this 10% gain as the standard measures are not able to compensate for losses of their unique ecological value. Extensive compensation requirements must be well met within the developers’ biodiversity gain plan to obtain planning permission.

This blog post delves into the list of irreplaceable habitats outlined by the government, what makes them irreplaceable, their wildlife, benefits, and conservation efforts being made to protect them. It explains their role within the BNG policy and future directions.

What are Irreplaceable Habitats

Habitats are irreplaceable when they host unique, special ecosystems that if destroyed cannot be replaced. This means that special areas of nature must be protected and clearly outlined as irreplaceable to avoid losing precious ecosystems that we are unable to recover.

These tend to have high levels of biodiversity including endangered, endemic and rare species due to the lack of resilience in their habitats. These habitats must be protected to allow for their vital historical, cultural and ecological continuity.

It’s crucial that mass habitat destruction from development, climate change, pollution and agriculture must not be a threat to these ecosystems, so many are protected under European and UK legislation to avoid habitat loss.

Examples of Irreplaceable Habitat

Ancient Woodland

Ancient woodlands appear all across the UK, earning the title when the areas have been continuously wooded in England and Wales since at least 1600 AD, and in Scotland 1750 AD. They’re largely protected under various planning policies in the UK such as the NPPF (National Planning Policy Framework). Their microhabitats, like loose bark, hollows, sap runs and rot holes, give them a rich site biodiversity that supports an array of wildlife such as deadwood and ancient trees.

They provide fantastic research insights on long-term ecological processes, and are publicly accessible for recreational and education activities.

Various restoration projects have involved the reintroduction of native species, such as the dormouse, red squirrel, and woodland wildflowers, as well as controlling invasive species, like the rhododendron, himalayan balsam and grey squirrel.

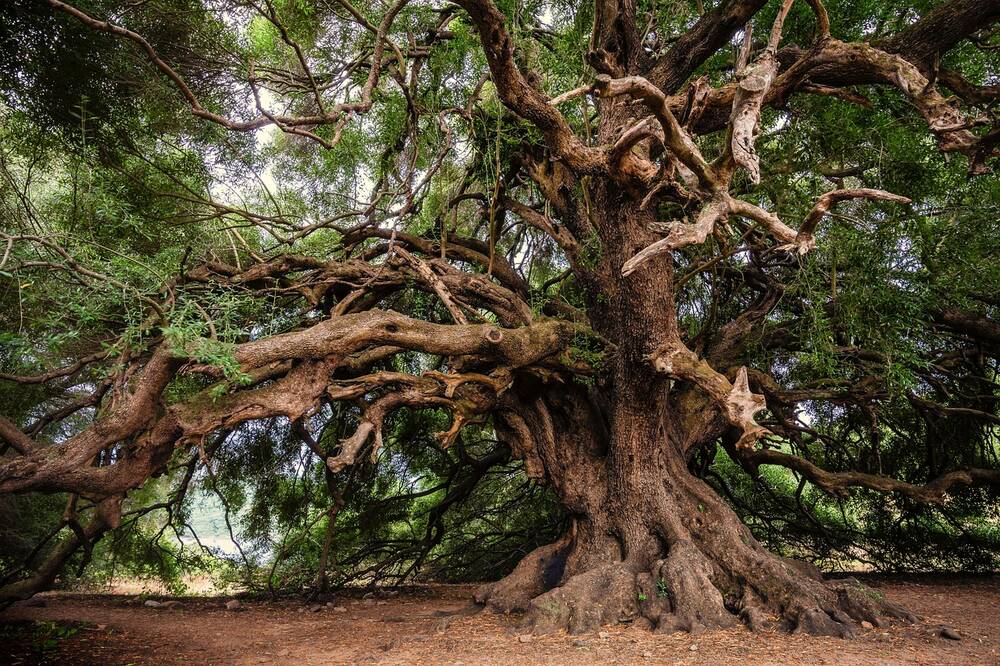

Ancient and Veteran Trees

Typically a few several years old, ancient trees will have wide, hollow and decayed trunks with complex canopies. Veteran trees tend to be less old, only displaying some of the characteristics of ancient trees.

These beautiful natural symbols of history and time are usually cultural landmarks, especially when they come stand-alone in fields and parks where their unique ecological qualities are emphasised.

For example the Major Oak in Nottinghamshire is estimated to be 1,000 years old, linked to the tales of Robin Hood, and in Scotland, the Fortinghall Yew stands as one of Europe’s oldest trees at over an impressive 5,000 years old.

Blanket Bogs

Usually in upland regions, a blanket bog is a waterlogged peatland in situations where rainfall overpowers evaporation leading to a buildup of peat (a surface layer of organic soil mostly from decomposed plant materials) over thousands of years. The buildup can be several metres deep.

These major carbon sinks help mitigate climate change, filter pollutants, reduce flooding and maintain the quality of water.

They can date back to the last Ice Age, and are categorised as SSSIs (Sites of Special Scientific Interest) and SACs (Special Areas of Conservation). Many conservation attempts have been made to restore and protect the precious ecosystems, such as blocking drainage ditches, re-wetting programs and reintroducing native vegetation.

Coastal Sand Dunes

Along coastlines, these dynamic sandy ecosystems are when dunes have formed over long periods of wind and wave action which deposit sand. They host ranges of biodiversity such as the sea holly, marram grass and dune wildflowers.

Norfolk, South Wales and Merseyside have sand dunes, some centuries old, and always changing due to our constant wind and waves. They host the slow worm, sand lizard, skylarks, dune tiger beetles, sand wasps and rabbits.

They are at threat from trampling, climate change, development and invasive species, however are protected legally to stop extreme threats from enacting harm. In conservation, fences can be added to prevent trampling, and native vegetation will be planted to encourage robust, resilient ecosystems, not without removing invasive species.

Limestone Pavements

Formed across millions of years through glacial action and rainwater erosion, limestone pavements are found in upland areas, mostly in Cumbria, the Yorkshire Dales and some areas in Wales. They were formed around 11,700 years ago with glaciers in the last Ice Age.

They resemble a paved surface, consisting of flat limestone blocks and deep fissures. This unique nature provides irreplaceable habitats and microhabitats for plants like the rock rose, herb Robert, and limestone fern, birds like the wheatear and falcon, and bats roosting in crevices.

They contribute heavily to geological stability and carbon storage, but have threats from quarrying, recreational damage, climate change and agriculture. They are legally protected, and routinely see conservation efforts in recognition of their ecological and historical value.

Lowland Fens

Fens are wetland habitats with nutrient-heavy, waterlogged soils, and a fen is lowland when it is low-lying, typically near sea levels where water accumulates. This creates saturated soils that support a range of biodiversity such as reeds, orchids, birds, amphibians, invertebrates and mammals.

Fens mitigate floods, purify water, store carbon and support other essential ecosystem services. In 17th century East Anglia, many Dutch engineers were hired by British landowners and to drain the fens for agricultural purposes, utilising new Dutch technologies.

Now, restoration efforts involve re-wetting fens that are drained to restore their natural hydrological and ecological value. Focuses are on replanting natives such as sedges, marsh orchids and reeds, as well as removing invasives like canary grass and purple loosestrifes.

Mediterranean Saltmarsh Scrub

Along the coasts of southern UK, these scrubs occur where freshwater and saltwater mix in sheltered coastal areas. They home varieties of biodiversity, such as glasswort and sea lavender plants, or redshank, avocet birds as well as invertebrates.

They offer invaluable coastal protection such as their thick vegetation reducing the energy of waves and salt-tolerant plant roots stabilising soil levels, curbing erosion.

It bears cultural significance in salt production, grazing and fishing, and saltmarshes are central to coastal economies.

At threat from coastal development, rising sea levels, storms and agricultural runoff, saltmarsh scrub sites are also heavily legally protected and subject to various conservation and restoration measures.

Spartina Saltmarsh Swards

These are coastal habitats largely dominated by Spatrina grass which contributes to the unique biodiversity value of the sites. They appear in estuaries, mudflats and habitats where accumulation of sediment has resulted in ideal Spatina growth conditions.

The grass has rapid colonisation and is crucial in protecting shorelines and preventing erosion. Redshank, oystercatcher and curlew are wading birds that inhabit the swards, and brent geese, dunlin and redshank are migratory birds that will visit to utilise the irreplaceable ecosystem.

Irreplaceable Habitats and BNG

Biodiversity Net Gain is a policy affecting all ongoing developments in England. It means that developments will only obtain planning permission from their subsequent LPAs if they can prove that they will deliver a 10% gain to the nation’s biodiversity levels, overcompensating for any biodiversity lost at the development site.

A biodiversity metric calculates how much will be lost, and exactly how much should be added to meet the mandated gain. The planning authority will only pass a thorough planning application that explains its plans to restore, recreate or replace the biodiversity in detail.

This is either achieved through on-site delivery such as green infrastructure, off-site delivery through sourcing and purchasing biodiversity units from landowners such as by using Gaia’s leading BNG Marketplace, or finally through statutory biodiversity credits as the last resort option.

These 8 habitats—ancient woodlands, ancient and veteran trees, blanket bogs, limestone pavements, coastal sand dunes, Spartina salt marsh swords, Mediterranean saltmarsh scrubs and lowland fens—are all legally exempt from BNG. They are excluded from mandatory BNG 10% requirements, instead needing bespoke compensation.

Developments impacting these habitats must have incredibly well justified reasoning and suitable compensation, and planning permission will only be granted in exceptional circumstances.

Responsibilities for Developers with Irreplaceable Habitats

It’s key for developers to be responsible when they have to handle irreplaceable habitats. They should be prepared to identify the habitat as early in the processes as possible to enact the mitigation hierarchy most effectively.

This means that avoiding harm to irreplaceable habitats should be achieved first, before minimising the harm, and finally restoring the harm that has been caused due to complete lack of options.

Compliance with legal frameworks like the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and Biodiversity Net Gain regulations is mandatory, and developers should be responsible in maintaining public transparency and fair stakeholder engagement, such as local communities, environmental groups, and regulatory authorities.

Protecting Irreplaceable Habitats

Irreplaceable habitats demand special protection and much higher priority within the development planning processes. Strong justification must be demonstrated in order for local authorities to actually pass the development plans.

Compensation strategies must be specially tailored depending on the habitats and its ecological, cultural and historical value must be sustained.

Debates on Irreplaceable Habitats & What Is Included

Irreplaceable habitats can be a contested topic, as their unique ecological value is quantified by governmental regulations and policies which are frequently debated.

Governmental regulation outlines that a habitat is irreplaceable due to its uniqueness, species diversity, age and rarity, however conservationists propose that ancient grass, though lacking the rarity and diversity of others, should also be deemed irreplaceable and adequately protected. Many critics call for a broader inclusion of habitats.

In Biodiversity Net Gain, irreplaceable habitats are exempt from the 10% gain as their loss cannot be compensated adequately by standard measures. A contested area is their bespoke compensation strategies for any unavoidable impact, involving rigorous justification that must meet public demand.

The Future of Irreplaceable Habitats

In the future, irreplaceable habitats will likely have stricter enforcement covering a wider selection of habitats, such as ancient grasslands.

There will be broader public awareness through outreach programs and education on the sheer value of these habitats and their need for protection through policy and conservation.

Ongoing scientific research can sharpen our understanding of their ecological value, alongside robust monitoring systems tracking their health, and incorporating methods of climate change resilience as deeper levels of protection.

More Information

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/irreplaceable-habitats

https://cieem.net/information-on-irreplaceable-habitats-added-to-biodiversity-net-gain